Traditional Site for Digging for Ark Souvenirs

Intrigued by ruins atop Mt. Cudi (the original Mt. Ararat) that had for millennia been association with the ship of survivors of a great flood by multiple Middle Eastern cultures and religions, I made a few attempts to reach the site. The famous British explorer Gertrude Bell had reached it in 1911, as had three Germans, but to my knowledge no previous American. The earlier explorers had all had local guides and peaceful conditions. Now, there was now an ongoing military conflict on and around the mountain that made it extremely difficult to visit. I finally succeeded in 2013 but was stopped en route at machine gunpoint by the PKK, taken to another location, and held and interrogated for some time before finally being released and permitted to make the climb.

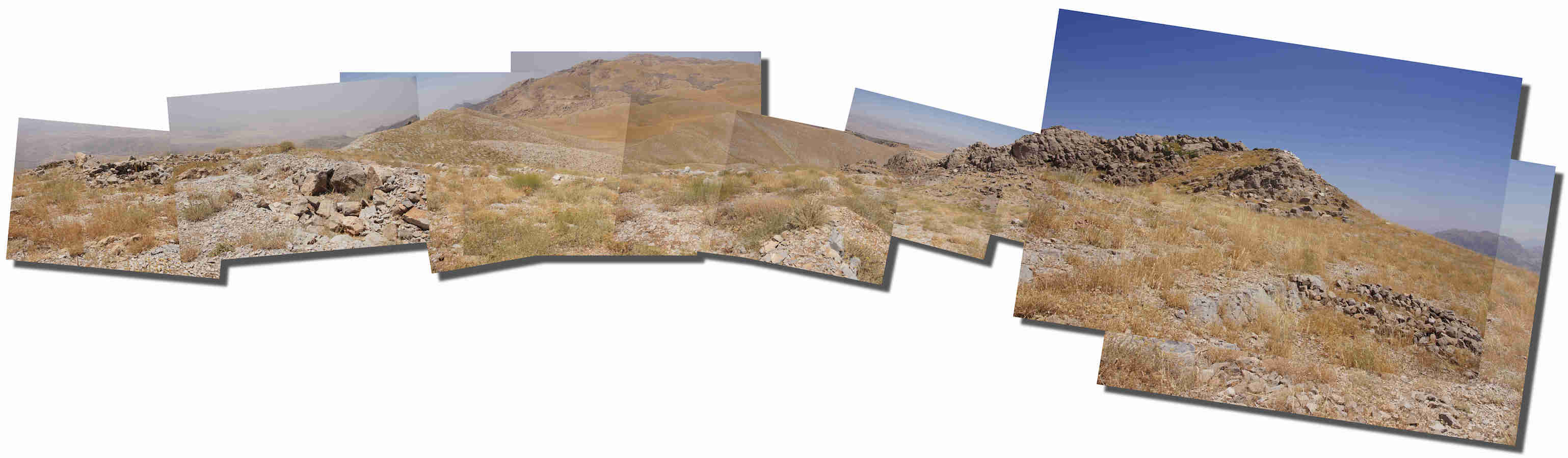

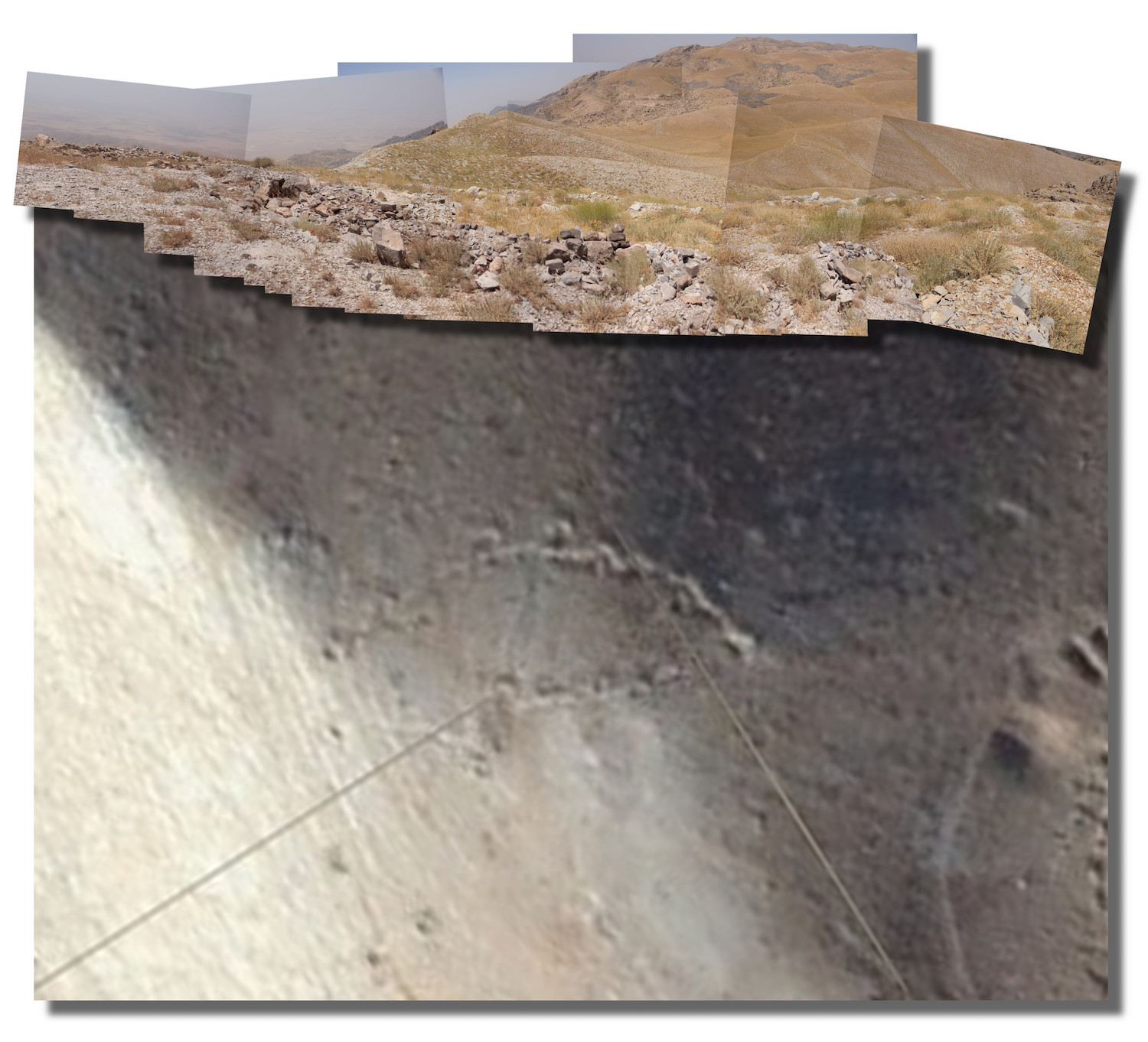

The post below shows my first efforts at photos on and around the site.1 This is an attempt to get a better sense of the structure that for millennia was said to hold the Ark of Noah (or Nuh or Utnapishtim). I had been too close to it and hadn’t gotten a good overview. So, I went back through my photos, tagged any potential overlap, and fashioned a simple panorama:

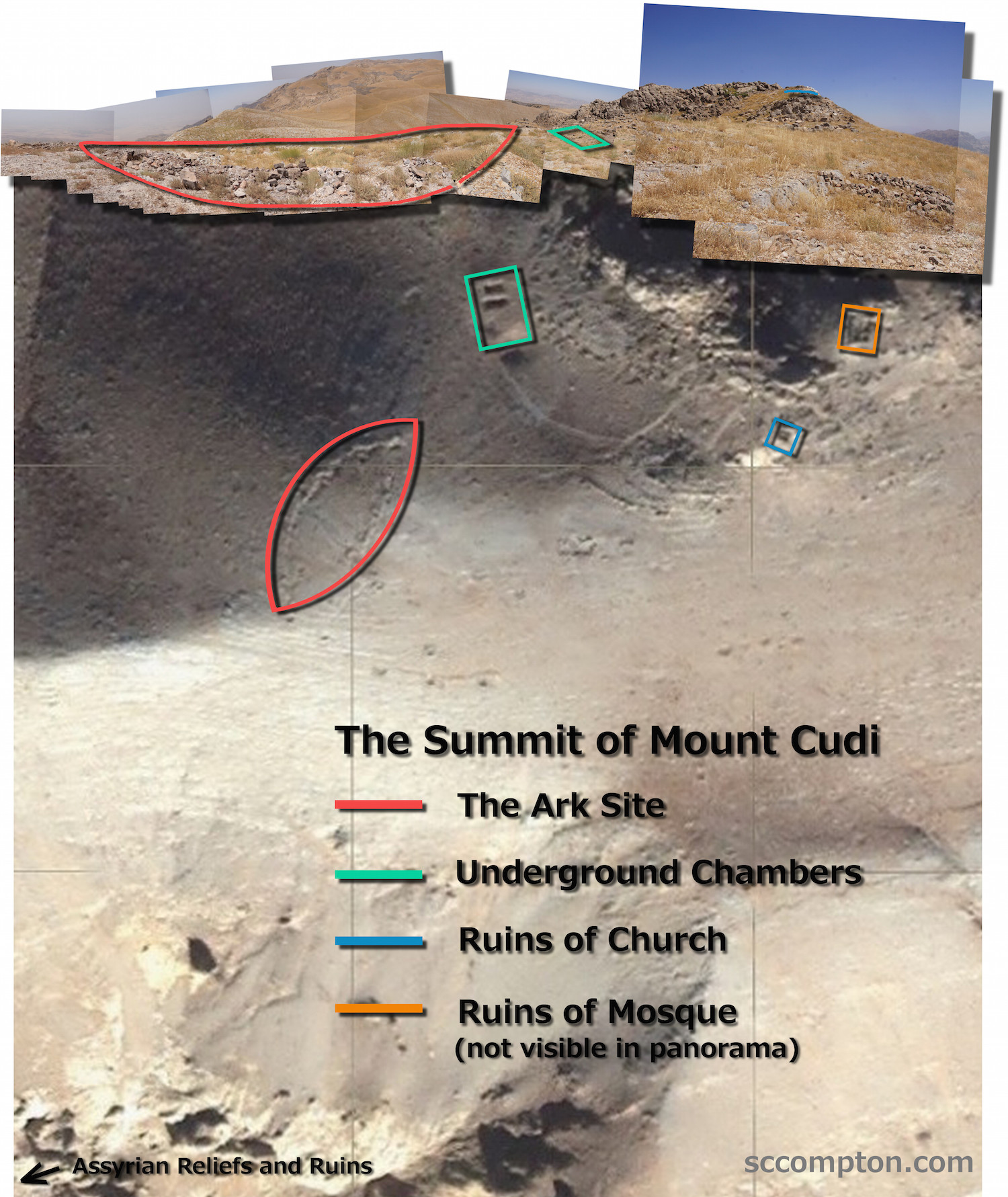

So what are we looking at here? The ancient Babylonians report cutting off pieces of the Ark to use as magical amulets.2 The Assyrian emperor Sennacherib climbed this mountain in 699 BC and was said to have had idols carved from the Ark.3 In 537 AD, the Christian emperor Justinian allegedly used its wood for the doors of his great cathedral, the Hagia Sophia. And in the seventh century, Caliph Umar “took the Ark from the two mountains and made it into a mosque.”4 Even after the exposed portions had been stripped away, pilgrims came annually for centuries, digging up relics of the Ark as part of a religious festival: “On descending the mountain they bring with them some remains of the Ark, which, according to their assertion, is still deeply buried in the earth.”5

What remains now is a ship-shaped depression, visible on satellite photos, but unfortunately trapped for decades in an active conflict zone. On finally reaching it (exhausted from the climb, extreme thirst, and the ordeal with the PKK guerrilla fighters), I found that the formation now consists largely of holes, trenches, and mounds of dirt and rocks, apparently the result of centuries of digging in the rocky ground. Some of the mounds (likely more recent) consist of dirt mixed with stone. But in most cases, centuries of rain appear to have washed the dirt away, leaving mostly stone in the piles along the old pits and trenches.

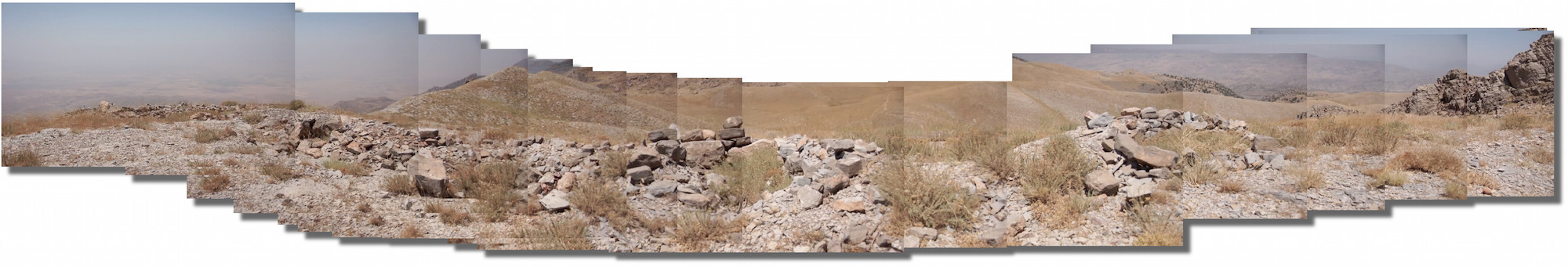

Unfortunately, because I took photos from different positions as I explored the structure, it was difficult to find exact matches, and the foreground was incomplete. So I went through my videos and found this pan along its east side, which would be the foreground of the above panorama:

Using screenshots from the video, I created a second panorama:

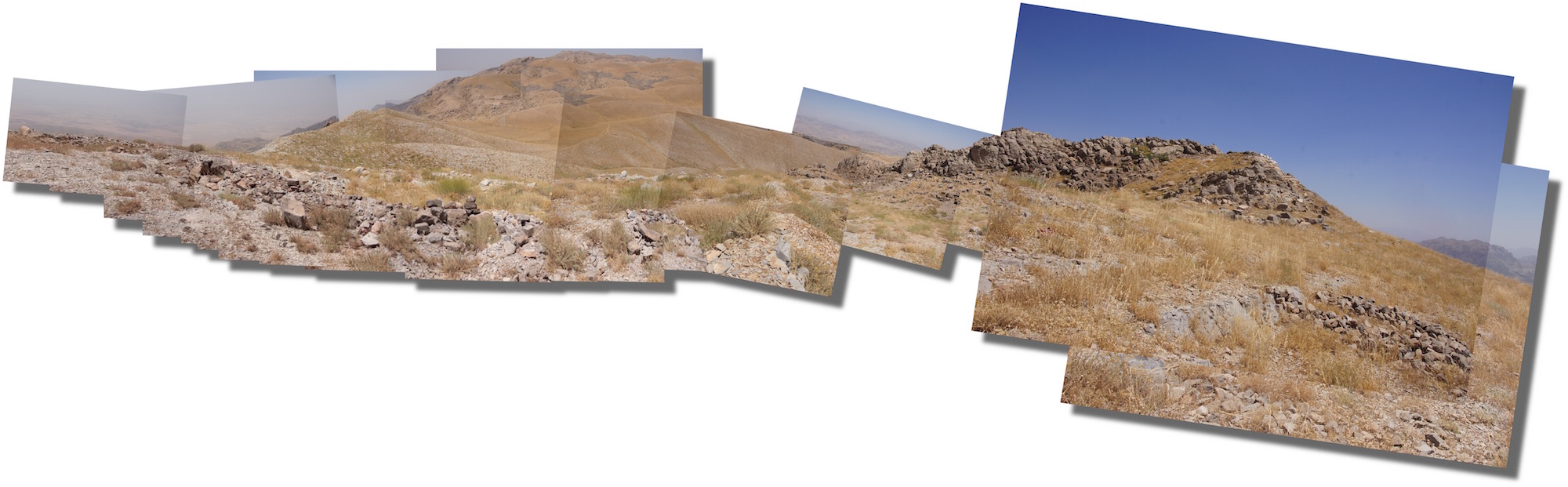

And, since the left side of this panorama mirrors that of the initial panorama, I was able to combine them into a more complete view of the structure:

Here is the completed panorama overlaying a satellite view of the same spot (courtesy of Bing Maps) and annotated:

And a last image to close the post, just the Ark:

I’ll try to get future posts up in a more timely fashion. This one took much longer than expected. Just piecing together that first 30,000-pixel-wide panorama slowed my laptop to a glacial pace and crashed it repeatedly, eliciting some unfortunate outbursts from its operator.

NOTES

1. On the importance of this site: “If the Ark of Noah should ever be discovered, it would be the greatest archaeological discovery of all time.” —Gilbert Hovey Grosvenor, editor of the National Geographic Magazine for 55 years. My earlier posting of the first individual photos of the structure can be seen here. In them, I failed to capture the entirety of the structure, due to its enormous size, the rough topography, the ground cover, and extreme time constraints. I have attempted to remedy that in this new post by joining multiple photos and a video into a high resolution panorama of the site.↩

2. The 3rd century BC Babylonian priest and historian Berosus wrote of the Great Flood: “It is said that there is still some part of this ship in Armenia, at the mountain of the Cordyaeans [Kurds]; and that some people carry off pieces of bitumen, which they take away, and use chiefly as amulets for the averting of mischiefs.”↩

3. Babylonian Talmud: Tractate Sanhedrin, folio 96a. Sennacherib inscribed his own image and an account of his ascent here on the side of Mount Cudi. He also left multiple stone prisms that boast of his ascent on his return trip from laying siege to Jerusalem. The story of Sennacherib is the first time that the Bible mentions “Ararat” after saying that the Ark landed there. The context strongly suggests that Mount Cudi was the Biblical Mount Ararat, and Jewish tradition identified Cudi as Ararat at least as early as the 11th century visit to the region by Benjamin of Tudela. See the following citation.↩

4. Benjamin of Tudela, The Itinerary of Benjamin of Tudela, trans. Marcus Nathan Adler (London: Philipp Feldheim, Inc., 1907), 33. Mount Cudi is the Turkish spelling of Mount Judi, the traditional name of this mountain, which is named in the Quran as the place where the Ark of the prophet Nuh rested. ↩

5. J J. Benjamin II, Eight Years in Asia and Africa: From 1846 to 1855 (Hanover, 1863), 93-94.↩

November 6, 2014 @ 7:08 pm

Not enough words to describe how brilliant this post is! Amazing photos and well-written synopsis of your adventures to climb Mt. Cudi (i.e., you’re a true polymath). –Alison

November 8, 2014 @ 5:04 pm

Very informative article. Thanks for sharing this Stephen. I wasn’t even aware there was a site where the remains of Noah’s Ark are rumoured to be. Very exciting to think what could be found here if it weren’t in such a hostile area. Looking forward to hearing more updates on this! : )

November 8, 2014 @ 8:06 pm

I love the adventure that you embarked on, in order to find the ark. The photographs are outstanding. I do believe that Noah’s Ark is in that location, but I’m unsure as to whether or not this will ever truly be proven. Nonetheless, It’s an intriguing subject and I’m eager to learn more.

November 9, 2014 @ 1:54 am

This is a fascinating post. To think that you were there where the Ark once rested. I’ve been lucky enough to be able to travel, and never get used to the idea of walking through historical sites – castles where knights and lady’s in waiting once lived, the place where Jesus walked, etc. If only places could talk – Your pictures do though. Thanks for sharing them.

November 10, 2014 @ 9:50 am

First of all I wanna say that it would be a special find indeed to find the ark of Noah! I myself would be especially excited to tell my husband about it because he is the worlds biggest skeptic. I believe in God and don’t need proof of his existence, unlike many skeptics out there. A discovery such as this would be a serious “I told you so” moment lol.

April 20, 2021 @ 4:22 pm

Great article and site! I would tend to agree with many of the same findings and mountain for the resting of the ark, with one exception. The red outline is not the ark site itself, but a boat-shaped chapel. It’s only about 175 feet long and 60 feet wide, not fitting the biblical dimensions of the ark.

Rather, the ark most likely is the darkened outline and area where the bitumen-covered wood was found on the ledge just south of there. The boat-shaped outline of this structure/feature is approximately 450 feet long by 75 feet wide—fitting the dimensions given in scripture. I don’t know that any proper study of archaeology has taken place at that spot, but for my money, that’s where I would look.

Here you can see a 3D model of the mountain I’ve created and uploaded, with annotations to describe the archaeological features: https://skfb.ly/6VJ77